Meeting Nature as a Presence: Aldo Leopold and the Deeper Nature of Nature

Craig Holdrege

From In Context #36 (Fall, 2016) | View article as PDF

We were eating lunch on a high rimrock, at the foot of which a turbulent river elbowed its way. We saw what we thought was a doe fording the torrent, her breast awash in white water. When she climbed the bank toward us and shook out her tail, we realized our error: it was a wolf. A half-dozen others, evidently grown pups, sprang from the willows and all joined in a welcoming mêlée of wagging tails and playful maulings. What was literally a pile of wolves writhed and tumbled in the center of an open flat at the foot of our rimrock.

In those days we had never heard of passing up a chance to kill a wolf. In a second we were pumping lead into the pack, but with more excitement than accuracy: how to aim a steep downhill shot is always confusing. When our rifles were empty, the old wolf was down, and a pup was dragging a leg into impassable slide-rocks…. I was young then, and full of trigger-itch; I thought that because fewer wolves meant more deer, that no wolves would mean hunters' paradise. (Leopold 1949/1987, pp. 129-30)

With these words, the 56-year-old Aldo Leopold reflected back on an experience he had at the age of 22. It was 1909 and Leopold was leading a crew for the newly formed United States Forest Service that was carrying out an inventory of the locations, quantity, and quality of timber in Arizona and New Mexico.

After shooting the wolves, Leopold and his crew climbed down to the banks of the river and found the old wolf. She was still alive but unable to move. Leopold put his rifle between himself and the wolf, she grabbed the rifle in her jaws and then died.

We reached the old wolf in time to watch a fierce green fire dying in her eyes. I realized then, and have known ever since, that there was something new to me in those eyes — something known only to her and to the mountain. (Leopold 1949/1987, p. 130)

As he watched the light in those eyes disappear, Leopold met the wolf for the first time. For a split second he glimpsed the wolf as a being in its own right. The impression stayed with him. In a sense the wolf became part of Aldo Leopold on that day. And yet it took many years for the wolf to become a force in his thinking. He could still write in 1920, eleven years after the encounter: “It is going to take patience and money to catch the last wolf or [mountain] lion in New Mexico. But the last one must be caught before the job can be called fully successful” (quoted in Meine 1988, p. 181). Leopold was trained as a forester and was an avid hunter. Working for the Forest Service, his goal was, in part, to manage forests for the maximum quality and yield of timber. He held to the principle of “maximum use,” which for him included managing forests and other wild lands in such a way that they provided food for livestock, game (such as deer) for hunters, and recreation for people. Predators that killed livestock and game simply did not fit into the world view of the young forester and game manager. His thinking about nature was centered on human interests.

For most of 15 years following the encounter with the wolf, Leopold worked in the southwest (New Mexico and Arizona) for the U.S. Forest Service. He rode thousands of miles on horseback and observed first-hand the ecology, wildlife, and human use of the land in this arid part of North America. He also studied scientific literature and philosophy. These were years of expanding experience and thought. Leopold’s biography and writings reveal tensions, contrasting perspectives, and shifting alliances as his view of the world became more centered in nature’s concerns (see Meine 1988, Lutz Newton 2006).

In an unpublished 1923 essay, Leopold writes about the economic rationale for conservation: the wise use of resources will ensure their long-term service to humanity. It makes economic sense to take ecology into account in human planning and action. His years of observation showed him that overgrazing by cattle and sheep were causing widespread erosion and habitat destruction. “Erosion eats into our hills like a contagion, and floods bring down the loosened soil upon our valleys like a scourge. Water, soil, animals, and plants — the very fabric of prosperity — react to destroy each other and us” (Leopold 1923/1991, p. 93).

But in the very same essay he also disparages a narrow anthropocentric, economics-driven view: “In past and more outspoken days conservation was put in terms of decency rather than dollars” (Leopold 1923/1991, p. 94). He contrasts the economic perspective with a moral one that is rooted in something “felt intuitively,” namely that there is “between man and the earth a closer and deeper relation than would necessarily follow the mechanistic conception of the earth as our physical provider and abiding place” (Leopold 1923/1991, p. 94). Referring to the Russian philosopher P. D. Ouspensky’s view of the earth as a living organism, Leopold writes:

Possibly, in our intuitive perceptions, which may be truer than our science and less impeded by words than our philosophies, we realize that indivisibility of the earth — its soil, mountains, rivers, forests, climate, plants, and animals, and respect it collectively not only as a useful servant but as a living being . . . (Leopold 1923/1991, p. 95)

The respect for nature and the desire to protect the earth into the far future is rooted for Leopold in a budding recognition of the living quality of the earth as a whole. And while he remained comfortable until the end of his life expressing ecological relations in quantitative and causal terms (he speaks, for example, of the “land mechanism”), he also strove to give voice to a depth of nature that transcends the grasp of the kind of scientific ecology in which he was steeped.

Leopold’s description of killing the old wolf is part of his seminal essay “Thinking Like a Mountain,” which he wrote when he was 57 (in 1944) and which was published only in 1949, a year after his death. He begins the essay with vivid imagery:

A deep chesty bawl echoes from rimrock to rimrock, rolls down the mountain, and fades into the far blackness of the night . . . . To the deer it is a reminder of the way of all flesh, to the pine a forecast of midnight scuffles and of blood upon the snow, to the coyote a promise of gleanings to come, to the cowman a threat of red ink at the bank, to the hunter a challenge of fang against bullet. Yet behind these obvious and immediate hopes and fears there lies a deeper meaning, known only to the mountain itself. Only the mountain has lived long enough to listen objectively to the howl of a wolf. Those unable to decipher the hidden meaning know nevertheless that it is there, for it is felt in all wolf country, and distinguishes that country from all other land. It tingles in the spine of all who hear wolves by night, or who scan their tracks by day. Even without sight or sound of wolf, it is implicit in a hundred small events: the midnight whinny of a pack horse, the rattle of rolling rocks, the bound of a fleeing deer, the way shadows lie under the spruces. Only the ineducable tyro can fail to sense the presence or absence of wolves, or the fact that mountains have a secret opinion about them. (Leopold 1949/1987, p. 129)

What is this quality of nature Leopold is depicting here? The wolf is no longer only a predator to be killed for our benefit. It is also not simply part of the food web or a top-level predator. It is a presence in the landscape. This presence makes itself known through all the interactions between wolves, deer, spruce trees and rocks. What reveals itself in the interactions is not what the conventional science of ecology speaks of:

Everybody knows, for example, that the autumn landscape in the north woods is the land, plus a red maple, plus a ruffed grouse. In terms of conventional physics, the grouse represents only a millionth of either the mass or the energy of an acre. Yet subtract the grouse and the whole thing is dead. An enormous amount of some kind of motive power has been lost. (Leopold 1949/1987, p. 137)

When Leopold uses the phrase “motive power” to characterize the grouse, he is pointing to the living presence of the bird that ramifies into the larger whole of the landscape. I could also say, perhaps more appropriately, that he sees the landscape expressing itself in and through the grouse or through the wolf.

In an essay written near the end of his life, the “Song of the Gavilan” (a river in Mexico), Leopold’s writing culminates in a powerful portrayal of the living presence — the music — that permeates the whole of nature. But you have to learn to perceive it:

This song of the waters is audible to every ear, but there is other music in these hills, by no means audible to all. To hear even a few notes of it you must first live here for a long time, and you must know the speech of hills and rivers. Then on a still night, when the campfire is low and the Pleiades have climbed over rimrocks, sit quietly and listen for a wolf to howl, and think hard of everything you have seen and tried to understand. Then you may hear it — a vast pulsing harmony — its score inscribed on a thousand hills, its notes the lives and deaths of plants and animals, its rhythms spanning the seconds and the centuries. (Leopold 1949/1987, p. 149)

Here Leopold articulates a sensory-supersensory experience of the natural world. This is no longer science in the ordinary sense; one commentator calls it “poetic science” (Berthold 2004). It is clear that this kind of experience cannot be described in discursive language. Leopold applies the artistry of his writing to paint vivid images that suggest what is at work in nature. It is something, he says, that we can perceive if we learn to attend in the right way.

Leopold hints at what is needed to prepare for such experiences. You need to “live here for a long time.” This means to connect yourself with a place by being in it and being wakefully attentive, by noticing and taking in what’s happening. Since his childhood Leopold loved being in nature — observing, thinking, camping, riding, hunting. He knew places firsthand and he was attentive.

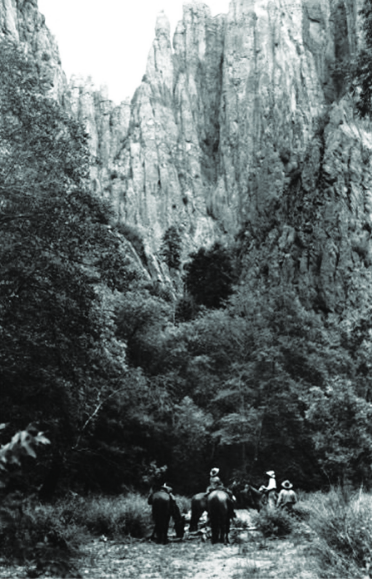

The Gila wilderness in New Mexico, 1922. It became the world's first designated wilderness area in 1924; Aldo Leopold played an instrumental role in its formation. (Photo by W.H. Shaffer)

But this is not enough — you “must know the speech of hills and rivers.” What kind of knowledge is he talking about here? As a forester and game manager, Leopold had learned much about nature, but he always saw things in terms of their service to human beings — the value of trees for timber or deer for hunters. This is not the speech of rivers or hills, but of human beings and their needs. As an ecologist, Leopold learned to see how hills, rivers, trees, fires, cattle, deer, and wolves are all dynamically interwoven. Increasingly he didn’t just think about nature in terms of human needs, but he was able to think with nature.

But to know the “speech” of nature requires a further quality of thinking. Conventional ecological thinking, which Leopold had secure command of, considers nature’s beings and happenings in terms of causes and effects, and aims to explain all the connections. Leopold could never have written about the wolf or the landscape of the Gavilan River in the way he did had his mind been confined to seeing nature only in terms of causal links, food webs or energy flows. In these essays he is portraying and not explaining nature. To do this you have to step back from causal thinking, renounce the drive to explain, and focus your mind on what shows itself, what speaks in the connections. This is the kind of thinking that permeated Goethe’s efforts in science.

Perceiving and portraying relations in nature so that they speak is no simple matter, especially for anyone who is fully at home in discursive scientific thought. This is what is remarkable about Aldo Leopold. He acknowledged and gained from everything that conventional science could contribute to understanding, but he was also able to go beyond it. Leopold points to a way of strengthening our ability to learn the speech of nature when he encourages us

to “think hard of everything you’ve seen and tried to understand.” We’ve dwelt in a landscape, attended to it, and striven to understand its speech. Now we turn inward and we revisit in our mind’s eye our experience of all that we have taken in. We vividly imagine the wolf, the stars and the river as presences. We move in a concentrated fashion through our thought-filled experiences. I know out of my own experience that this activity forges a deeper connection with the world and it becomes a source of insight.

And then, if we become inwardly quiet and actively attentive, we may in a moment of heightened awareness perceive some feature of the deeper nature of nature — the pulsing harmony, the forceful presence of the wolf, or the motive power of the grouse. This is “thinking like a mountain.” But here the thinking has become a form of perceiving. When we have activated our own being in this way, the presences of nature can express themselves through us. The experience of the sensory world becomes a spiritual experience.

Such experience also becomes the basis of an ethical relation to the natural world. Leopold recognized that “no important change in ethics was ever accomplished without an internal change in our intellectual emphasis, loyalties, affections, and convictions” (Leopold 1949/1987, pp. 209-10). He himself evolved inwardly, and toward the end of his life he formulated what he called a land ethic:

A land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for his fellow-members, and also respect for the community as such. (Leopold 1949/1987, p. 204)

Our humility as human beings grows when we experience other creatures or qualities in nature as beings or presences in their own right. We can then see ourselves, as Leopold did, as part of a community of beings in which all members enjoy our respect. And this connection with other beings is strengthened each time when, in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s words, we have moved beyond a merely profane relation to the sense world and have truly “given heed to some natural object,” perceiving that it is more than meets the eye.

Aldo Leopold (1887 to 1948)

Aldo Leopold was one of the greatest ecological thinkers and conservation biologists of the twentieth century in the United States. His collection of essays, A Sand County Almanac, was published 1949 only after his untimely death from a heart attack at the age of 61. The book contains the mature fruits of his thinking and writing. It became an important source of thought and inspiration for the environmental movement that began in the 1960s, and it has been a widely read classic ever since (with over two million copies sold).

After completing his studies in forestry at Yale University, Leopold worked for the U.S. Forest Service in the southwestern United States. Here his practical and theoretical knowledge of ecology grew and took form. While initially focusing on forest management, he became increasingly concerned about human destruction of natural habitats. He was active in various conservation organizations and played a key role in the establishment of the first wilderness areas within national forests. From 1924 until his death he lived in Wisconsin. In 1933 he became the first professor in the newly formed discipline of Game Management at the University of Wisconsin, which under Leopold became in 1939 the department of Wildlife Management. In 1967 the department was renamed Wildlife Ecology, reflecting the shift in attitude toward wild animals that Leopold in his own lifetime went through.

This article is a slightly revised version of an article published in Elemente der Naturwissenschaft (#104, 2016). It is loosely based on a talk Craig gave at the “Evolving Science” conference in the fall of 2015 at the Goetheanum in Dornach, Switzerland.

References

Berthold, Daniel (2004). “Aldo Leopold: In Search of a Poetic Science,” Human Ecology Review vol. 11 (3), pp. 205-14.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo (1844). Essays: Second Series. (Many editions available.)

Leopold, Aldo (1949/1987). A Sand County Almanac. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Leopold, Aldo (1923/1991). “Some Fundamentals of Conservation in the Southwest.” In Flader, S. L. and J. B. Callicott (Editors), The River of the Mother of God and other Essays by Aldo Leopold. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Lutz Newton, Julianne (2006). Aldo Leopold’s Odyssey. Washington: Island Press.

Meine, Curt (1988). Aldo Leopold: His Life and Work. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.