African Impressions (Part 2)

Craig Holdrege

From In Context #9 (Spring, 2003)

In our last issue of In Context, Craig’s article “African Impressions (Part 1)” described some of the landscape and animal experiences he had during his trip to Botswana last August. In this article he adds several more impressions.

Encounters with People

My nineteen-year-old daughter, Christina, and I arrived at the Johannesberg airport at three p.m. on August 4th, after a fourteen-hour direct flight from New York. Tom and Peggy (my brother and sister-in-law) were there to meet us. Now, giddy with jet lag, I had to drive a rental car for three hours on the “wrong side” of the road in a car with the steering wheel on the right. First of all, I needed to find my way out of Johannesburg onto the correct highway. We'd reserved a room in a hotel in Nylstroom, which lies on the way to Botswana, northeast of Johannesburg.

Luckily, we were not left on our own. There were two Bantu policemen in the parking lot and I asked them for directions. They described how to get onto the right road, and repeated themselves to make sure I got it. But they evidently read the confusion on my face and, instead of becoming exasperated with this American tourist, one of them said, “just follow us; we'll drive ahead of you and at the corner where you need to turn right onto the highway, we'll wave you goodbye.” We jumped into our vehicles and drove off—winding around for a few miles (I'm sure I would have missed the turns) and then they stopped and waved. We waved back and were off. It was great to have the first human encounter in Africa to be so warm and friendly. And that with policemen in Johannesburg, when all we'd heard about Johannesburg was how dangerous it is!

On August 6 we spent the morning in the town of Serowe, Botswana. Botswana has been a democratic country since 1966 and was never a European colony — a rarity in Africa. Serowe was the home of the chief, Seretse Khama, who was instrumental in creating the independent democratic constitution in 1966 and became the country's first prime minister. It's hard to describe a town so different from any settlement we know in America or Europe. Small mud huts with thatched roofs, cinderblock huts, and sometimes larger dwellings spread out over a quite a large area in a seemingly haphazard fashion. One paved road traverses the town, with small dirt roads branching off into the areas with huts. Often one or two huts with an outhouse are surrounded by a woven branch fence. It's the dry season and the dark red earth is parched and barren. Occasional trees provide shade; some are brown and shedding their leaves.

At one end of town there is a modern market place surrounded by shops. It is newly built with structures in red brick. There is a large open area paved with paving stone where people set up their stands to sell clothes, vegetables, fruit, and so on. Walking through the market place we realized that we were the only white people — Serowe is not a tourist town. To our minds we should have stuck out like sore thumbs, but only the little children really stared at us and saw us as welcome curiosities. It was my first experience of being in such an obvious minority, and yet the concept of minority didn't seem to fit, because I didn't feel alienated from the “majority.” The people at the market stalls, the tellers at the bank, the cashiers and stockers at the small supermarket were all very friendly and natural to us. Our skin color didn't seem to matter. We may have been out of place, but we weren't made to feel it.

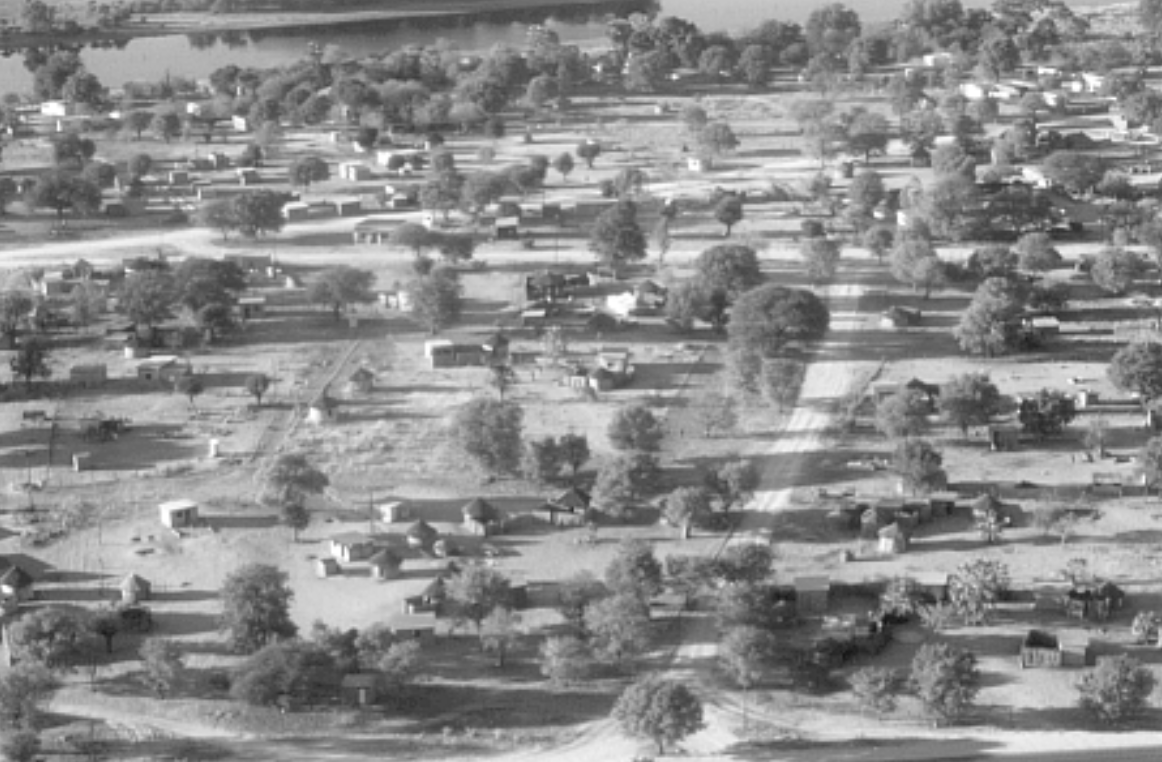

An aerial view of the town of Maun, Botswana. We were flying in a small plane from Maun into the Okavango Delta. As in other towns, the small huts spread out over large areas, in this case near the banks of the Thamalakane River (top of picture). The round crowns of the Mopane trees provide shade.

In Maun, Botswana, we visited a local basketmaker's shop. The shop (about 12 feet by 20 feet) was right next to the hut in which the owner lived. The owner was a woman in her late thirties, who started a cooperative of basket makers. The beautiful baskets were done in a traditional style and made from leaves of the fan palm. The leaves were locally harvested, dried, and colored with indigenous plant dyes. The designs were mostly traditional, but she showed us some of the new designs she was making with the help of computer graphics software. A surprising marriage of simplicity and technology!

The owner had learned basket making and taught the trade to others — mainly women — who then became part of the cooperative. She spoke with joy about this work and the importance for her people of having a local economy and meaningful work to support the needs of a family. She was strong, clear, forthright, and warm. We were impressed by her and glad to know that in buying baskets from her, we were in turn supporting families in Maun.

Bashi is a young man in his twenties who was our guide for two days in the Okavango Delta in Western Botswana. (This is a remarkable inland delta that carries water from a river in Angola and then fans out and disappears into the edge of the Kalahari desert.) Bashi was quiet and unassuming in all interactions and at the same time he radiated strength and confidence. When leading us through the delta waterways, he not only noticed every bird, plant, or tree, but also knew their names and what they are used for. Drawing our attention to an aquatic "eye dropper" plant, he removed the swollen stem beneath the flower and demonstrated its use as an eyedropper. The liquid that drips out, he said, is very good for treating eye inflammations. He also broke off the stem of a water lily and showed us its jelly-comb-like inner structure; he then used it as a straw and said it is an excellent water filter. I could give many more examples of Bashi’s broad knowledge.

Our guide Bashi reaching down to gather fruits from an enormous Baobab tree. We were on an island in the Okavango Delta with dry savannah vegetation.

But it was not just his knowledge that impressed us about Bashi; it was his whole bearing. When we climbed out of the makorros (traditional-style dugout canoes, now fashioned from fibre glass to protect the tree species they were originally made from) to walk around on one of the dry delta islands, Bashi led us through the bush. He said we should follow him and make as little noise as possible. As he walked ahead — barefoot and quiet — you could see how his attention was out in the surroundings. He wasn't here looking there. He was part of what was going on around him. In watching him, I realized how far I am from such an “immersion consciousness.” He was with the bird sounds, he was with the tree leaves. And then, he had the gift to bring this “being there” back to us and was able to point out and describe things in very concrete detail.

At one point Bashi had a big grin on his face. He had heard and then seen a Pell's Fishing Owl. This owl — well-known in birder circles — is the only owl that eats fish, hunts during the day, and whose wings make audible sounds when flying. People come from far away and try to catch a glimpse of the owl. Till this day Bashi had only heard them. Now he saw one, and right afterwards another one. The latter was perched up in the boughs of a tree. Silent, and with its brownish feathers matching the color of the bark, it would have escaped our notice altogether. But Bashi pointed upward and there it was, perched on a branch, looking down at us with its black eyes. We watched it for what seemed to be a long time (and was probably a minute or two) and then it flew off, spreading its large wings and somehow maneuvering between the limbs of the trees. The next day we saw another Pell's Fishing Owl on a different island. Bashi could hardly believe it. I'm glad these two days also gave him something to remember.

Animals

August 8, afternoon, Okavango Delta. Out for a walk on the grassy flats bordering the belt of trees along delta waterways, I saw movement around one of the large trees. Grey forms — about the size of large house cats with long tails — scattered, some disappearing into the darkness of the undergrowth, others moving up into the tree's crown. I stood still, looked, and waited. At first I couldn't see anything, but then noticed a monkey peering at me. It was a vervet monkey. Another one appeared a moment later. These two monkeys moved onto that branch of the tree closest to me, about 15 feet above my head. They kept their eyes on me at all times while in continual movement. They would cock their heads quickly to one side, move back and forth, and cock their heads the other way. Then one would suddenly jerk its upper body forward and glare at me. Through this body posturing the monkey, it seemed, was trying to tell me something. But to me — ignorant human — it was primarily a comical sight. I read later that these gestures are part of the monkeys' territorial behavior.

Their hands and fine, long fingers were also making continual small nervous movements, while the tail was held out straight and long behind them. At times their long, sharp canines were visible, protruding below the upper lip. It's clear that every movement these monkeys make and every posture they take on means something in the context of their life in the troop (varying in size from eight to twenty individuals). They live in a world not only of feeding, fleeing, etc., but also in one of gesture, expression, and complex communication. I can take in and enjoy this rich world, but cannot (yet?) read the meaning it carries.

August 11, at the edge of the Moremi wildlife reserve. We got up at six and went to a wild dog den. Richard, our guide Anne's son, drove us there. He is working with Tico McNutt, an American biologist who has been studying wild dogs (Lycaon pictus) in Botswana since 1989. We were fortunate enough to be able to spend a morning at a den.

Richard told us that there were 12 adult dogs and yearlings as well as 12 pups in this pack. We arrived at the den and stayed about 20 to 30 feet away from the openings to the underground den, perched in our land rover. The researchers don't want the dogs to get used to human presence, so we humans remained part of "truck presence" for the dogs. We spotted one dog lying under a tree dozing in the shade. It had very large ears and was about the size of a coyote. She had a beautiful coat — brown, black, and white. She remained lying about 50 feet from the den. Since no other dogs were around, Richard surmised that they were out hunting, and the pups would be hidden in the den. When a pack has pups, usually one or two adults remain behind whenever the rest go out to hunt. Richard showed us drawings of the other adult dogs in the pack. Each dog has a unique color pattern and is thereby recognizable. In this way, the researchers can follow each dog over the course of its life.

After about 45 minutes, one adult dog, and then another, came running through the trees and bushes of the dry savannah to the den. We heard a kind of barking and suddenly all the pups scurried up out of the den and bubbling life came with them. The pups were about ten weeks old and a foot high at the head. The “oohs” and “aahs” of us humans broke out — the puppies in their playful, furry innocence struck a warm chord in our souls.

Two wild dog pups in front of their den opening, sparring for a piece of meat.

The pups surrounded the adults and yelped; the yelp was a whiny, high-pitched sound. Often a pup yelped while lying on its back right under the snout of the adult. As with the monkeys, much gesturing was going on. The adult proceeded to regurgitate part of its kill. Immediately the pups were tearing and pulling at pieces of the bright read meat, and sometimes having a tug-of-war. The meat was probably from an impala, a staple of wild dogs in this area. When one pup got a piece of meat, it would run away with the meat in its jaw and try to eat, only to be disturbed by a den mate who tried to tear the prize away for itself.

One after another the other members of the pack returned. There was continual activity — regurgitating, feeding, sparring, chasing, and playing. An astounding sight. The pups especially engaged one another; the adults would often lie down to digest — until they were disturbed by one of the little ones.

Soon a group of black vultures flew in. They walked toward unclaimed pieces of skin. Ever curious, a pup would move toward a vulture, which, in turn, would peck at the pup who then ran away, only to start approaching again soon. When a vulture became too aggressive, an adult would jump up and lunge at it, which caused the vulture to fly off. Then it would circle and land again.

I knew that wild dogs are social animals living in packs. But to actually see the intimate and manifold interactions between the pack members and the relation of the pack to the vultures was a real eye opener. The pack consisted of individual animals, but they were all so interconnected in their behavior that it seemed more like observing one whole, rather than an agglomeration of parts.

After leaving the wild dogs, we drove into the Moremi wildlife reserve to a new campsite. There we encountered the hippos, elephants, giraffes, and lions I described in In Context # 8.

Original source: In Context #9 (Spring, 2003, pp. 5-8); copyright 2003 by The Nature Institute